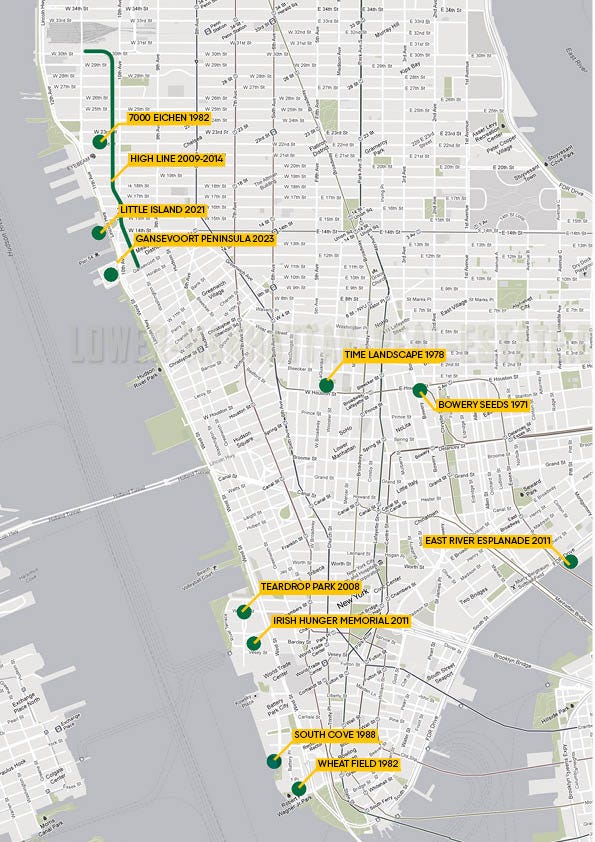

Lower Manhattan hosts a history of late 20th century site-specific artworks interpreting nature in the city. Some extant, some ephemeral, these urban works by conceptual artists Hans Haacke, Agnes Denes and others foreground vegetation’s symbolic, productive, projective and transformative capabilities. As designers and artists engineered and built fertile sections to support life over piers, railway lines, and other infrastructures, they advanced technical know-how in landscape architectural technology. A map of the project locations is at the end of this post.

Simultaneously, a different sort of natural public space in the city was lost: the fertile section of imagination. Conjured by individual and collective imaginations in the open, undeveloped, wild, and abandoned spaces that once populated lower Manhattan, these places to explore, transgress and trespass, imagine and dream, are endangered and essential public spaces. Can we preserve these ambiguous places to explore, transgress and trespass, imagine and dream in the city? Or is it their very precarity that draws our longing and anticipatory nostalgia?

One Place After Another

Works from 1969-2010 directly influenced the ideologies and design technologies of the next generation of landscapes on the west side of Lower Manhattan: Chelsea Cove (MVVA Inc, 2010), Phase Three of the High Line (James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, 2014), Little Island (Heatherwick Studio and MNLA,2021), and Gansevoort Peninsula (James Corner Field Operations, 2023). This string of public and private parks on old piers and docks were built after the removal and reconstruction of the elevated west side highway as a surface boulevard. More on these parks and this recent era of urban succession in a future post.

Seeding the City: Early artist works

As Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring(1962) and the first Earth Day (1970) brought increased awareness of environmental issues, nature moved from artist’s subject to artist’s medium. Nancy Holt and Mary Miss created site-specific works that directly engaged natural materials and processes. Until this time, Lower Manhattan's parks and landscapes reflected a picturesque and Victorian view of nature, constructed on grade. However, starting in the 1970s, new critical site works highlighted ecological processes, the physical and symbolic work of ruderal species, and invented new relationships and technologies to create nature in the city.

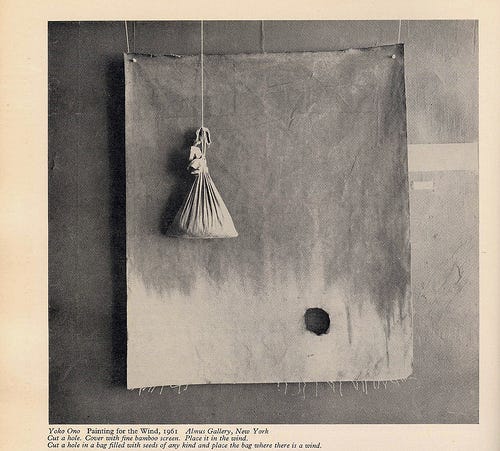

Three ephemeral works in Lower Manhattan raise metaphoric-political questions through occupation and process: Painting for Wind (Yoko Ono 1969), Bowery Seeds (Hans Haacke 1971), “Wheatfield - A Confrontation, Battery Park Landfill, downtown Manhattan, 2 acres of wheat planted & harvested, summer 1982” (Agnes Denes 1982)

Yoko Ono’s Painting for Wind (1969) featured a small packet of seeds hung from a larger piece of paper, and text instructing one to cut a hole in the paper, then cut a hole in the bag, and place it in the wind (Masters 2008). Bowery Seeds and Painting for Wind are examples of early works of ruderal aesthetics in lower Manhattan. They foreground ideas of latency, ambience, and emergence: the seeds lie dormant in the soil; the atmosphere provides sun, water, and windborne seeds; the seeds then germinate on a given fertile substrate as formed by the artist.

Bowery Seeds: Hans Haacke (1971). Hans Haacke placed soil on the roof of his Bowery studio and later photographed the vegetation growing on the pile. In published project images, the small pile of rough soil, green forbs, and grasses dominate the foreground in sharp focus, with a blurred urban context in the background. Here, the idea of site is defined by the soil, as the locus, and wind as a mechanism of seed distribution. As a site work that renders visible urban energy flows, Bowery Seeds sits between his contemporaneous works of institutional critique that also “daylighted” otherwise unseen patronage relationships (Haacke’s cancelled 1971 solo show at the Guggenheim, Shapolsky et al Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 traced the financial relationships of the museum’s trustees and a notorious slumlord) and ecological systems (Rhinewater Purification Plant, Krefeld, Germany, 1971).

“Wheatfield - A Confrontation, Battery Park Landfill, downtown Manhattan, 2 acres of wheat planted & harvested, summer 1982” (1982). Denes’ ecological line of works began in 1968 with Haiku Poetry Burial/Rice Planting and Tree Chaining/Exercises in Eco-Logic (Spaid 2012). The work “calls attention to our misplaced priorities and deteriorating human values.” It is a deliberate act of “wasting” real estate through occupation (Spaid 2012).

Denes installed the work on a site that would later become Battery Park City in lower Manhattan. To prepare the site, Denes and her crew cleared, amended the soil, and dug furrows, sculpting a fertile section within the “rusty metals, boulders, old tires and overcoats” of the landfill. In photographs of the work, Denes walks through a sea of wheat with the mountainous towers of Wall Street in the background, echoing the traditional landscape painting compositions of agriculture and farm laborer foregrounded against sublime mountain wilderness.

Wheatfield set the precedent for inserting provocative, productive-symbolic landscapes in the unrelenting impermeability of lower Manhattan, mocking the notion of “highest and best use” of land. By highlighting the aesthetics of agricultural labor and making art of clearing, soil preparation, planting, and harvesting, she brought attention to the precarity of the earth’s agricultural landscapes and ecosystems. Wheatfield planted these ideological concerns on two fallow acres in the financial center of the world. Like her contemporary Mierle Laderman Ukeles (1978, Touch Sanitation), Denes sought to foreground the quotidian and hidden life support processes—food production, garbage collection—at play in Manhattan.

Framing the Past: Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape

Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape (1965, opened 1978) ushered in a wave of work where artists and designers reproduced fragments of landscapes in a postmodern ecological pastiche, later seen in The High Line, Teardrop Park, and South Cove. These works use the spatial and technical methods of landscape architecture of the 19th and 20th centuries’ picturesque and modern parks, to create landscape vignettes representing plant communities at a particular moment of history, location, or ecological succession.

Time Landscape, at La Guardia Place and West Houston, represents the landscape of pre-colonial Manhattan. Commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time Landscape is a living museum diorama, complete with a didactic plaque, where passersby can witness the growth and evolution of plantings behind an enclosure.

Sonfist consulted with ecologists at MIT to develop a suitable substrate and plant list, as “there were no established guidelines for creating an urban forest in the 1960s, our collaboration was crucial in crafting an immersive experience that reflected the rich biodiversity of a natural forest. “ (Lorenzo, 2025) Sonfist and volunteers amended the site’s soils and planted a small grove of oak and beech saplings, and a thicket of dogwood and cedar. Much of Sonfist’s work centers on the resilience and precarity of ecological systems. The works are insertions that assert, as critic Jonathon Carpenter writes about Sonfist’s ecological works, “Nature asserts itself as itself. It exists alongside people occupying space with the same legal status as they do: humans and nature together equally.” (Carpenter 1983).

A Section to Imagine: Joel Sternfeld’s Walking the High Line

Abandoned in the late 1980s, the elevated railway viaduct of the West Side High Line Railway evolved into a wild urban meadow. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, urban explorers reached the surface from the street via secret access points, or descended from adjacent buildings. Joshua David and Robert Hammond formed Friends of the High Line in 1999 to preserve the structure from demolition and lobby for its conversion to an urban linear park. In 2000, photographer Joel Sternfeld, with permission from railway operator CSX, spent a year photographing the High Line’s landscape and context.

Sternfeld’s images are the establishing shots in the new ruderal aesthetics and an example of the “aesthetic implications of the new paradigm in ecology” (Simus 2008). On the High Line of the 1990s, several cycles of ruderal vegetation and decay thickened the soil profile, with organic and inorganic debris filling the gaps between the stabilizing rail ballast. The additional soil provided diverse substrates for more species to thrive. This thin carpet dominate the images, but the physical vegetation is only half the picture. Here, the ruderal vegetation was a placeholder for the projection of any number of fantasies. Sternfeld’s images have two parts: the vegetated path and the sky and skyline, creating two spaces for imagination. There are no hints of the traffic below; the sky is overcast and dampened. The contrast of the vegetated carpet between the greens and desaturated context and sky creates “a pocket of scraggly disobedience” (Dion 2013) in Chelsea.

After publication, Sternfeld’s serial images of the High Line operated in a rhetorical capacity, attracting New Yorker’s attention to the viaduct’s precarity as an urban artifact. Friends of the High Line used the images for fundraising efforts and formed the backdrop renderings of the future landscape. One can draw parallels between Sternfeld’s images and the wilderness survey images used by lawmakers to promote the preservation of Western landscapes in the mid-19th century. In “Imaging Nature: Watkins, Yosemite, and the Birth of Environmentalism,” Kevin Michael DeLuca and Anne Teresa outline how folios of Carleton Watkins’ sublime images of Yosemite Valley circulated among the elite of the East Coast and government officials in Washington, DC. Watkin’s images provided Fredrick Law Olmsted with a shared visual referent for his campaign to preserve Yosemite Valley from destruction or private ownership (DeLuca, Demo 2000). Both Watkins's and Sternfeld’s images transported potential stakeholders to otherwise inaccessible sites and ultimately saved the places from demolition, and advanced its radical transformation as a legible, safe and predictable urban space.

The green glitch of the High Line in the otherwise unrelenting fabric of the city opened a space of collective imagination. For a brief time, no one person had a claim on the future of the High Line; its ownership was tangled and there were no speculative renderings. It was a rare, unoccupied space in Manhattan, open to transgression: physically through trespass, or virtually, via Sternfeld’s depopulated images. The images conjured a kind of virtual air rights that said: this land is everyone’s: dwell here for a moment, and imagine. In the essay “Walking the High Line”, Robert Hammond, in conversation with Alan Gopnik, spoke of the “hallucinatory” qualities of the space:

“The High Line is just a structure, it is metal in the air, but it becomes a site for everybody’s fantasies and projections… I just pray that, if they save the High Line, they will save some of the virgin parts, so that people can have this kind of hallucinatory experience of nature in the city” (Gopnik 2001).

The construction of the High Line Park resulted in a peculiar commercialization of the High Line’s space of imagination. As Sternfeld and the Friends of the High Line asked us to imagine what might “grow here”: today billboards for new condos beckon us to imagine living alongside the park–to virtually occupy the space through the purchase of viewing rights. Though Sternfeld’s pictures remain, the real ruderal landscape is long gone, leading one to consider if “imagination sections” could be preserved in cities, or does the power of these spaces lie in their ephemerality?

The Fertile Section: Advancing Landscape Technology

Ecologist Eric Sanderson, in his book The Manahatta Project, reconstructed the landscape ecology of pre-colonial Manhattan using historic maps and data. The peninsula’s landscapes were diverse and permable, organized by the underlying geology, featuring gradients of wet to dry, with lowland and upland conditions and biodiverse plant communities (Sanderson 2009). Manhattan’s urban topography today is sealed, paved with buildings, streets, and plazas, save for small pockets of permeability in parks and gardens, tree wells, and storm drain inlets.

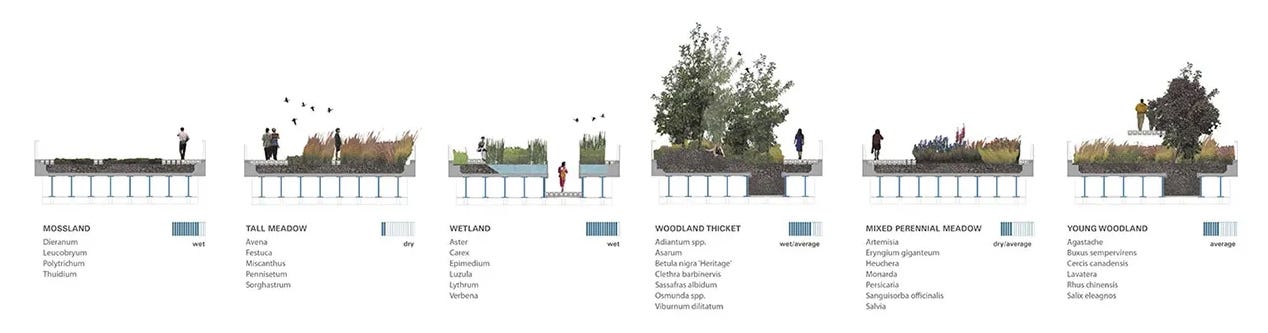

To create a fertile section for plants to thrive in the dense confines of Manhattan, one must dig, amend, decontaminate, sequester, support, and drain rainwater. How and what will grow is determined by the material composition and dimensions of this section, be it a cosmopolitan mix chosen for aesthetics, a collection of ruderal species, or a recreation of a pre-colonial Manhattan landscape.

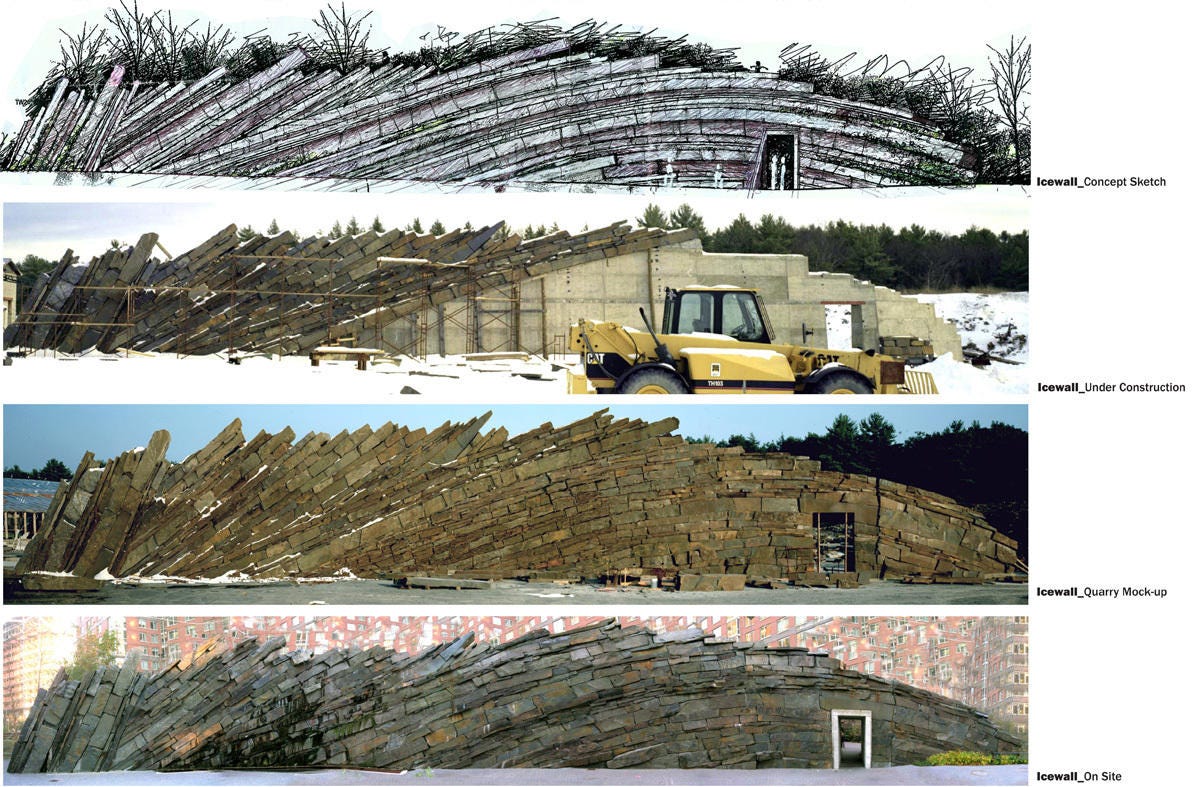

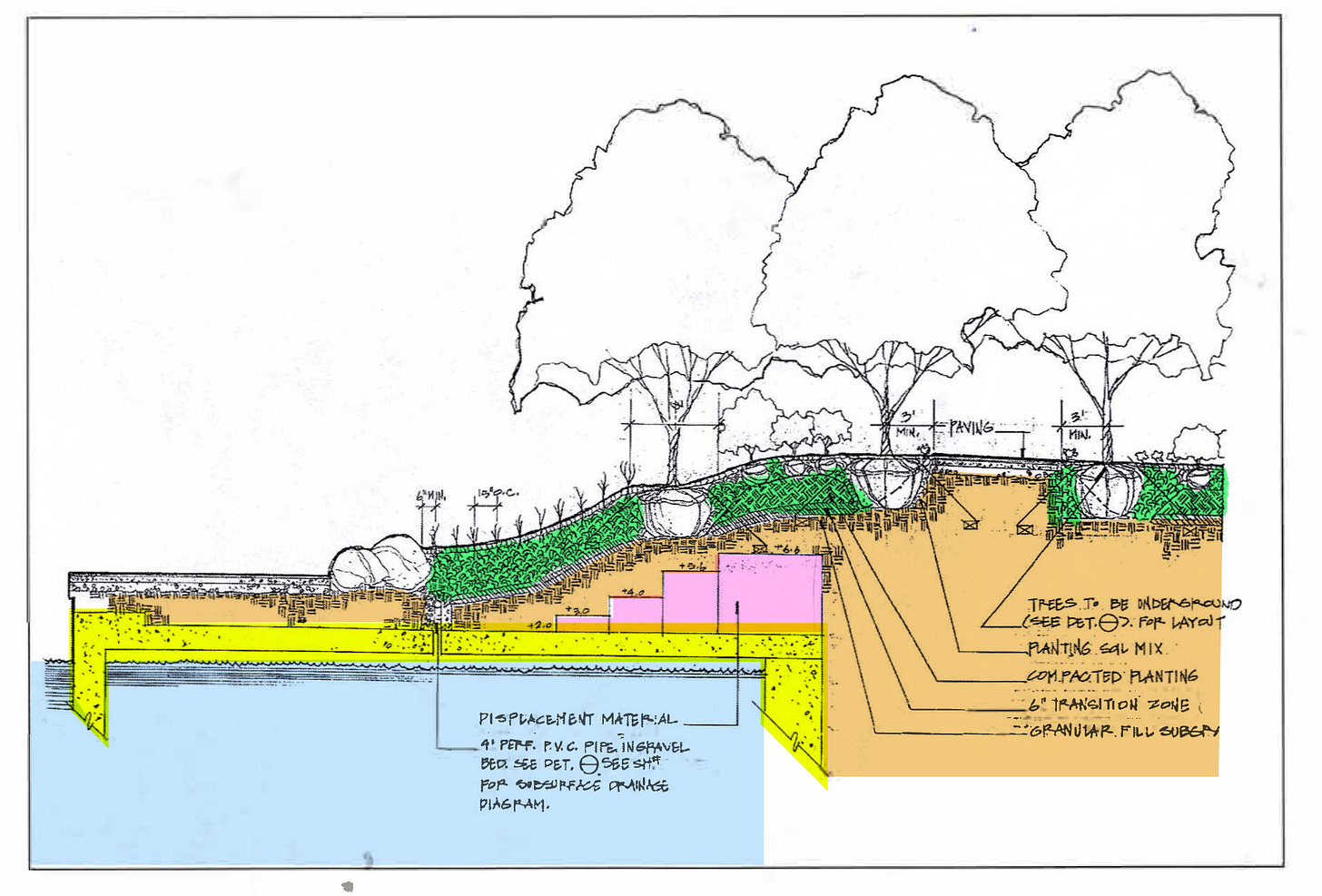

Lower Manhattan features several landscapes about landscapes, including South Cove (Childs Associates, 1985-89), Irish Hunger Memorial (Brian Tolle and 1100 Architects, 2002), Teardrop Park (Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates, 2004), and The High Line. Each evokes a distant and iconic landscape in a small plot in the city: an Atlantic seaside cove, a potato farm in County Mayo, Ireland, the Hudson River Valley, and an abandoned urban rail corridor, respectively. Though they differ in program and reference landscape, each relies on intelligent sectional detailing, surface materials, and vegetation choices to create an immersive surface that both represents nature and performs as nature (Bennett, 2014). The projects drew from technical advances in urban soil science, pioneered by Phil Craul (Craul, Lienhart, 1999, Kirkwood 1999).

The High Line Phase One

In 2004, Friends of the High Line selected four teams to submit comprehensive proposals for the High Line: Diana Balmori, Zaha Hadid and Skidmore Owings and Merrill; Steven Holl & Hargreaves Associates; and TerraGRAM (Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, D.I.R.T. Studio and Beyer Blinder Belle) and James Corner Field Operations & Diller Scofidio and Renfro (JFCO & DS+R). The JFCO & DS+R scheme High Line advances the sectional work of South Cove and incorporates state-of-the-art construction technologies, also hidden under complex layers of vegetation. First, between the rail structure and the new “green roof” landscape is a sandwich of protective waterproofing, drainage matting to capture and convey water, a layer of expanded obsidian gravel, and geotextile filter fabric to hold the soil in place. Next are the pavers tapering into combs, which play on a scale that both recalls and amplifies an image of wild grasses growing through cracks in the sidewalk (Field Operations 2004).

The waterproofing and water conveyance sections are indispensable to the technical success of the project, and the paving system provides material continuity and wayfinding cues. Above the technical section, interwoven with the pavers, is the enveloping environment of the planting. The designers thickened and modulated the soil profile to support the diverse plantings, and varied the height and density of the plantings that draw the eye to the detail of texture.

From Picturing Nature to Nature-Based Solutions

While the art and landscape works of the late 20th and early 21st century focused on symbolic representations of nature in the city, current projects evolve new nature-based technologies with traditional engineering elements like flood barriers to guard against sea level rise and storm surges. Succeeding the “representational” fertile sections are today’s ecological prosthetics, such as Living Breakwaters Scape and Ken Smith Workshop’s Mussel Beach at ERW Esplanade, demonstration projects of substrates and shellfish that might someday scale up to rebuild lost habitat and provide storm protection. As it has been the vanguard in art and music, Lower Manhattan also holds ground as a place to witness the many zeitgeists of nature in the city.

MAP

References

Bennett, K.E. 2014. "Beautiful Landscapes in Drag, the Material Performance of Hypernature." Journal of Landscape Architecture 9, no. 3: 42-53.

Blum, A. 2009. "Metaphor Remediation." Places Journal, September. https://placesjournal.org/article/metaphor-remediation-a-new-ecology-for-the-city/.

Beatrix, Lorenzo. "In Conversation with Alan Sonfist." Artofchange21. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://artofchange21.com/en/in-conversation-with-alan-sonfist/.

Carpenter, J. 1983. "Alan Sonfist’s Public Sculptures." In Art in the Land: A Critical Anthology of Environmental Art, edited by A. Sonfist, 151. New York: Dutton.

Craul, P.J., and J.R. Lienhart. 1999. Urban Soils: Applications and Practices. New York: Wiley.

David, J., and R. Hammond. 2011. High Line: The Inside Story of New York City's Park in the Sky. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Del Tredici, P. 2010. Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

DeLuca, K.M., and A.T. Demo. 2000. "Imaging Nature: Watkins, Yosemite, and the Birth of Environmentalism." Critical Studies in Media Communication 17, no. 3: 241-260.

Field Operations. 2004. High Line Proposal. New York: Friends of the High Line.

Gopnik, A. 2001. "A Walk on the High Line." New Yorker 77, no. 12.

Hauser, E. 2013. "An Elevated Plain." In A Field Guide and Handbook to the High Line, edited by M. Dion. New York: Printed Matter, Inc.

Kirkwood, N. 1999. "Abstracting Nature's Details: A Planted Path along a Cove." In The Art of Landscape Detail: Fundamental, Practices, and Case Studies. New York: Wiley.

Masters, H. 2008. "The Artist in Her Unfinished Avant-Garden." ArtAsiaPacific, no. 58: 142-149.

Paletta, A. 2014. "The High Line's Last Section Plays Up Its Rugged Past." Metropolis Magazine, October 14. http://www.metropolismag.com/Point-of-View/October-2014/The-High-Lines-Last-Section-Plays-Up-Its-Rugged-Past/.

Pickett, S.T., and P.S. White. 1985. The Ecology of Natural Disturbance and Patch Dynamics. Orlando: Academic Press.

Pickett, S.T.A., V.T. Parker, and P.L. Fiedler. 1992. "The New Paradigm in Ecology: Implications for Conservation Biology Above the Species Level." In Conservation Biology: The Theory and Practice of Nature Conservation, Preservation, and Management, edited by P.L. Fiedler and S.K. Jain, 65-88. Springer US.

Sanderson, E.W. 2009. Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. New York: Abrams.

Simus, J.B. 2008. "Aesthetic Implications of the New Paradigm in Ecology." Journal of Aesthetic Education 42, no. 1: 63-79.

Spaid, S. 2012. Green Acres: Artists Farming Fields, Greenhouses and Abandoned Lots. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center.

Stalter, R. 2004. "The Flora on the High Line, New York City, New York." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 131: 387-393.

Van Valkenburgh, M. 2004. High Line RFP: TerraGRAM. Request for Qualifications ed. New York.

Wright, A. 2013. Future Park: Imagining Tomorrow's Urban Parks. Clayton, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing.

Read on Substack