Architectural spaces of the carceral system include interrogation rooms, holding cells, courtrooms, prison complexes, and individual cells. This space is distilled to a five-dot, or quincunx, prison tattoo, the center dot representing the prisoner. The four dots at the perimeter represent the bounds of the prison cell.

Tied to these spaces in prolonged and oppressive relationships, prisoners and their relations lacks neutral spaces to mediate between the carceral system, family, and society at large. And so we ask, what is the architecture of such as space and where is it located? And what restitution, respite, or progression of thought, could occur there?

The theme of the 2018 Tbilisi Architecture Biennial was “Buildings Are Not Enough.” It was held in the city of Gldani, a microrayon (a Soviet-era, self-contained city extension, outside Tbilisi.) The event examined the optimism and rigor of the original microrayan plan, and the ways its citizens adapted the strict plan to individual and collective spatial and programming needs, through the transition from communism to the free-market capitalism of today. Gldani is also home to Prison #8, a high-security facility for men. Criminal justice and police reform in the early 2000s included a zero-tolerance enforcement policy that led to mass incarceration of men in Georgia, and the removal of criminal gangs that once enforced prison order, replaced by state officers. In 2012, the Georgian press released videos revealing systemic torture of prisoners by guards. This inescapable violence visited upon prisoners brought constant fear and trauma to those already serving sentences, and their loved ones. Massive protests, prisoner amnesty, and regime change followed the release of videos. Yet the state did not provide amnestied prisoners with psychological therapy or physical rehabilitation after their torture. The theme of the Biennial, “Buildings are Not Enough,” is thus threaded through the complexities of prisons and prison architecture; that physical isolation by secured architectural space is “not enough” to address all aspects of carceral realities.

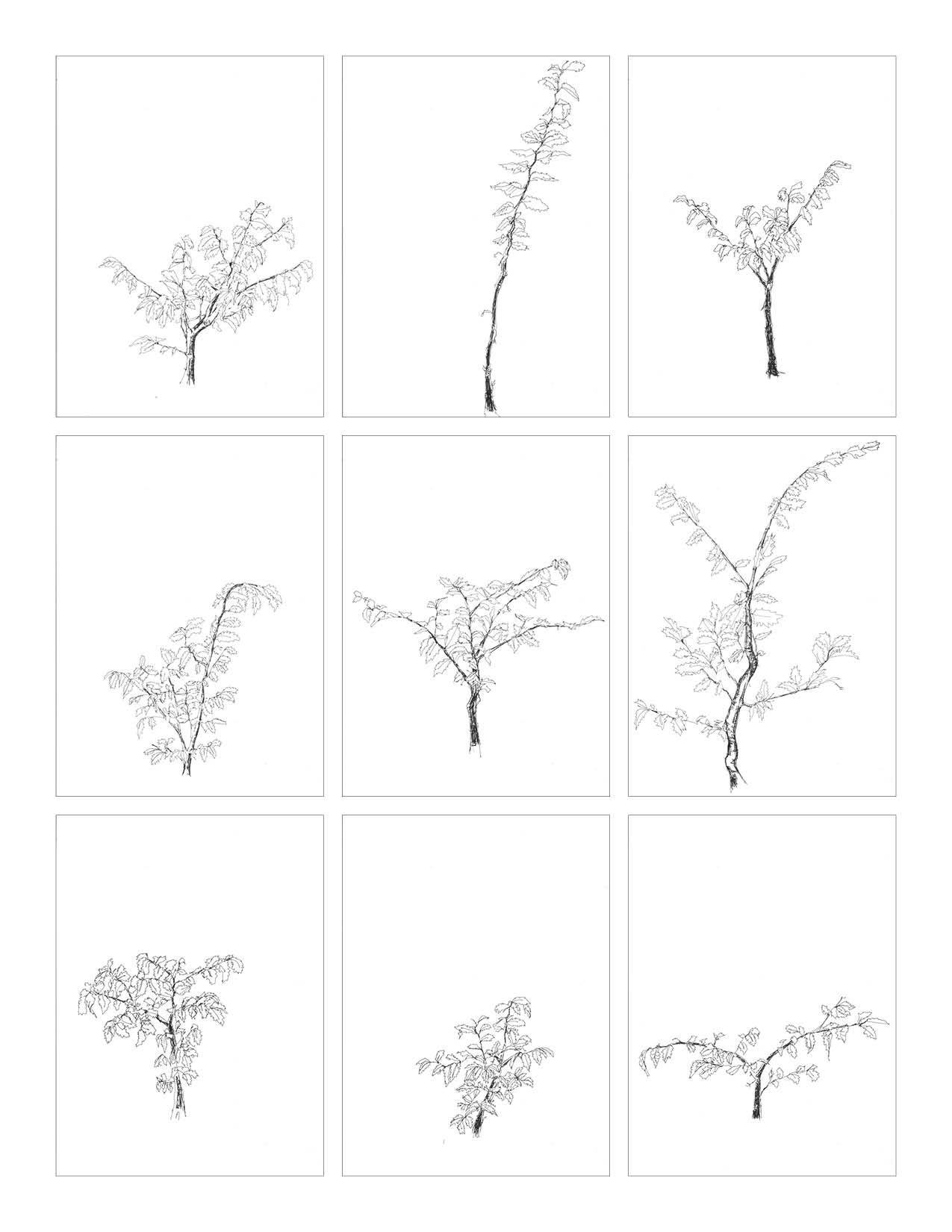

We propose a neutral space in the form of a garden adjacent to the prison bus stop. It serves as an intermediary space for visitors, workers, and released prisoners. The first planting is 25 Zelkova Carpinifolia trees in a quincunx pattern. Zelkova, or dzelis-kva, means “pillar stone” in Georgian. There is an open area at the center with a round table surrounded by a shade structure and seating, with an additional ring of benches at the edges. The tree at the center of each quincunx pattern represents the body of the prisoner, and the quincunx orchard echoes outward, representing the transfer of state violence throughout the family and society. Each year, another 25 trees are planted in this pattern with another table. Each drawing is of a Zelkova Carpinifolia seedling to be planted in the garden.

The garden is an evolving and material evocation of the point of the trauma of incarceration and its effects. It recognizes the experiences of citizens who were subject to extrajudicial and corporal punishment. Its existence provokes thoughts that although many elements of our society have advanced, the nature of crime, punishment, rehabilitation, and reintegration hover close, unresolved, and unrelenting.

Read on Substack